I had the pleasure of speaking at Magazines Ireland’s Publishing 360 conference in Dublin this week. Here’s a cleaned-up version of my speaker notes. It’s a long read, but I believe it captures the most important trends we’ve been covering here for the past several months.

The dynamics of the magazine publishing industry continue to change dramatically. Print advertising pages and circulation continue to fall across the industry. Digital revenues are growing but still haven’t made up for the drop-off in print revenues at many media companies.

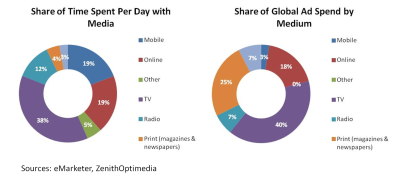

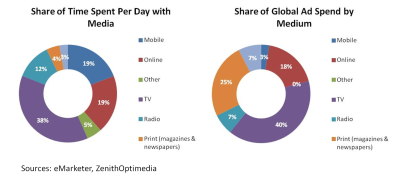

At the same time, ad spend still is not well aligned with consumer behavior. In 2013, consumers spent 38% of their media time on PCs or mobile devices, but advertisers spent just 21% of their ad budgets on those channels. If you just look at mobile, the gap is even wider: 19% share of time spent on mobile vs. 3% of ad spend. Digital advertising will account for just 13% of B2B marketing budgets in 2014.

There are some signs that marketers are taking steps to close the digital gap as the overall ad industry rebounds from the global recession:

– Growth rates for global advertising will improve from 3.9% in 2013 to 5.5% in 2014 to 6.1% in 2016, according to

ZenithOptimedia.

– Eurozone ad spend is expected to grow 0.7% in 2014 – its first year of growth since 2010 – rising further to 1.7% in 2016.

– Global online ad spend grew 16.2% in 2013, a rate that ZenithOptimedia expects to continue through 2016.

– Global online display expected to grow at 21% annually through 2016 – overtaking paid search for the first time in 2015.

Picking up the pace of digital transformation

In a recent report by EY, 70% of companies considered “digital leaders” in the media and entertainment industry – meaning those that get more than half of their revenues from digital – said they were willing to accept short-term revenue losses as they move up the learning curve for new media. And 65% said they are prepared to cut legacy media investments to support digital efforts.

That 50/50 split between print and digital revenues has become a symbolic milestone for many publishers. Only a handful, including IDG (2008), The Atlantic (2011), Wired (2012) and Forbes (2013), have announced publicly that they’ve reached the tipping point where digital revenues have surpassed print. At many other publications – large and small – the print engine still drives the revenue train.

We’re replacing print dollars with digital dimes. So you need to stack a lot of dimes to drive profits. For publishers that have been trying to protect their legacy print business while investing cautiously in digital, decisions on when and how to shift more resources toward growth channels are taking on greater urgency.

Here are six strategies that can help magazine publishers build a stronger foundation for a digital transformation.

1. Diversify in digital

Digital is not a product. Digital is an ecosystem of many channels – web, mobile, social – for building and serving your audience. The products and services you offer must be tuned to meet the diverse needs and activities of readers in each of these channels.

The best way to begin stacking dimes is with a diversified portfolio of products and services that generate either advertiser or reader revenue – along with a strategy for selling integrated, multi-channel programs.

Advertiser revenue:

- Display advertising

- Native advertising

- Programmatic

- Private ad exchange

- Sponsorships

- Affiliate marketing

- Marketing services

Reader revenue:

- Subscriptions

- Single-copy sales

- E-commerce

- Events

- Data products

- Apps

Some of these products are very traditional. Some – like native advertising, programmatic buying and private ad exchanges – are newer and more jarring to existing models. The key here is to experiment with lots of products and programs, measure them religiously, and redirect resources to the ones that show the most potential.

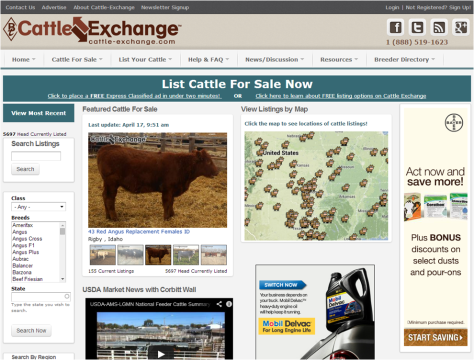

Selling cattle online

Farm Journal Media is a great example of how a B2B media company can successfully transition into the digital age with a mix of advertising, commerce and reader revenue. The 138-year-old publisher, whose agriculture magazines include Farm Journal, Top Producer and Beef Today, has aggressively built out its digital product offerings to create more inventory and more options for advertisers to reach farmers through a variety of web and mobile channels.

Over one recent 12-month period the company’s eMedia division released two dozen new products or feature enhancements, including an e-commerce site for cattle, an ad network and three mobile apps. Diversification has put the business on track to grow its revenues by 80% during its current five-year planning period.

2. Embrace the ‘brand as publisher’ trend

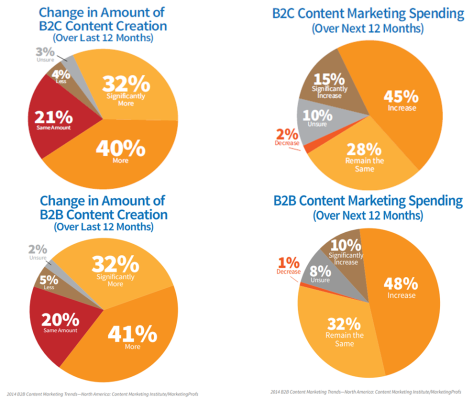

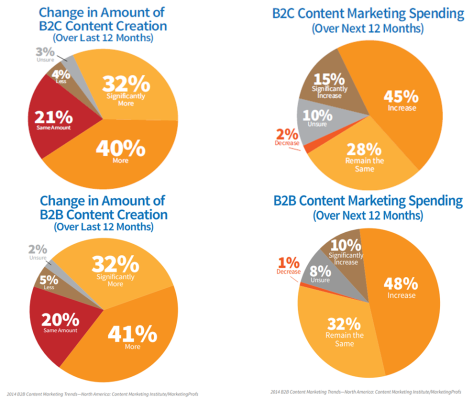

We’ve been writing about brands’ growing interest in creating their own content since eMediaVitals launched in 2009. The trend shows no signs of fizzling. According to the Content Marketing Institute, 90% consumer marketers and 93% of B2B marketers are investing in content marketing. Consumer brands are spending an average of 24% of their marketing budgets on content, 60% plan to increase spending over the next 12 months, and 72% are planning to create more content, including blogs, videos, articles, e-newsletters and case studies.

While some companies, from American Express and LinkedIn to Red Bull and Tesco, are aggressively building their own media brands, many more lack the skills and other resources needed to consistently create and distribute quality content. That’s why nearly two-thirds of marketers outsource writing, 4 out of 10 outsource design, and another 27% outsource content distribution.

Still, just 42% of B2B marketers believe they’re effective at content marketing. That’s a big opportunity for publishers. Some are already starting to capitalize. Meredith reported a 35% increase in operating profit at its content marketing group for the December quarter, compared with a 1% profit for its magazine group.

Tech publisher IDG has also created a successful marketing services business. The group offers a half dozen core service lines, from mobile marketing to lead nurturing. The group accounted for approximately one-quarter of the company’s total US revenues last year.

The native ad bandwagon

One high-growth area of marketing services is native advertising. As brands’ interest in native advertising grows, publishers have an opportunity to offer services not just for hosting these native ads, but for helping brands develop the content that goes into them.

Forbes is one brand that has invested heavily in native advertising with its BrandVoice program. BrandVoice participants doubled from 15 in 2012 to 31 last year. Those 31 brands published approximately 1,700 posts, which generated more than 11 million pageviews. In 2013, BrandVoice partners accounted for 20% of Forbes’ total ad revenue, a share expected to increase to 30% this year.

The UK’s Guardian is a more recent entrant into the native ad services space. In February the Guardian launched Guardian Labs, a group of more than 130 creatives, strategists, designers, video and content specialists who will develop content and products on behalf of brands. The Guardian’s first program was a seven-figure deal with Uniliver to develop and publish content, including interactive media and live events, on sustainable living.

But native is not just for big-brand publishers. Enthusiast publisher  Premier Guitar recently hosted a native ad campaign with online retailer Sweetwater. The publisher and brand co-hosted a live video program looking at the 24 coolest products introduced at the National Association of Music Merchants trade show. Each hour-long video segment included links to pages for each featured product – with a “learn more” link that clicked through to Sweetwater’s e-commerce site. The videos generated more than 200,000 views, and Sweetwater sales of guitars and related gear increased 50% year over year for March, when the program ran.

Premier Guitar recently hosted a native ad campaign with online retailer Sweetwater. The publisher and brand co-hosted a live video program looking at the 24 coolest products introduced at the National Association of Music Merchants trade show. Each hour-long video segment included links to pages for each featured product – with a “learn more” link that clicked through to Sweetwater’s e-commerce site. The videos generated more than 200,000 views, and Sweetwater sales of guitars and related gear increased 50% year over year for March, when the program ran.

3. Publish with a (re)purpose

Publishers need to continue to explore new ways to “skin the pig” – maximizing their editorial by repurposing content in different formats for different channels. We’ve come a long way from simply reposting print articles online – but there’s a lot more that can be done to leverage your editorial team’s interviews, event coverage and research.

Vox, the startup news site founded by former Washington Post blogger Ezra Klein, just launched a feature that lets users toggle between a story and the interview transcript from the story’s main source. It’s a cost-effective way to present content in two different forms. It gives more depth to readers who choose to dive deeper. And it provides another way to test editorial content to see what resonates with readers.

Ogden Publications, publisher of Mother Earth News, is also investing more resources in repurposing content. It regularly publishes excerpts from its extensive library of books, creating slide shows, blog posts and social media content that not only drives page views, but also drives traffic back to the book page.

Ogden CEO Bryan Welch recently told Bo Sacks that the company has hired a team of editors dedicated to “content proliferation”:

[Their assignment is] taking pieces of preexisting content, updating them and optimizing them for the web emphasis on engagement rather than page views. They have dramatically improved our efficiency in creating new products from repurposed content.

Publishers have also found success in aggregation and curation – in other words, repurposing other brands’ content. Upworthy has built a booming businesses off of third-party video content – to the tune of around 50 million unique visitors a month. It’s now beginning to monetize its model through native ads – in the form of curated brand videos.

Regardless of the source, the key to successful repurposing is creating quality content, not cheap knockoffs.

4. Turn print into something special

If circulation revenues are declining, it may be time to rethink the frequency and purpose of the print magazine.

“Print is not dead – though it will become increasingly coffee-tableish and collectible,” said Peter Sprague, chairman of Premier Media Holdings, which publishes Premier Guitar.

Publishers with deep archives can create a variety of theme-based special print editions that can generate incremental reader revenue. Ogden, for example, repurposes content for special print editions for the newsstand and periodic digital products like special e-editions. Playboy recently released an exact replica of its inaugural December 1953 issue, priced at $9.99, or $2 above the typical cover price.

Special issues, if done right, can generate so much buzz that they  outperform regular issues. Sports Illustrated’s Swimsuit issue has become a franchise in its own right; this year’s 260-page print edition contained 112 ad pages, a 14% increase from 2013. The 2013 issue sold more than 800,000 copies on newsstands, while overall newsstand sales averaged just over 68,000 per issue for the first half of 2013.

outperform regular issues. Sports Illustrated’s Swimsuit issue has become a franchise in its own right; this year’s 260-page print edition contained 112 ad pages, a 14% increase from 2013. The 2013 issue sold more than 800,000 copies on newsstands, while overall newsstand sales averaged just over 68,000 per issue for the first half of 2013.

The key is to get ahead of changing consumer habits. Special editions can create emotional bonds in a way that regular weekly or monthly issues cannot. Start thinking now about ways to combine an increase in special editions – theme-based issues, rankings, buyers’ guides – with a reduction in overall print frequency to improve profitability.

Waiting too long could doom a print franchise. Meredith recently announced that Ladies’ Home Journal would cease monthly publication after 131 years in print. The publisher’s plan to turn the magazine into a special interest publication sold on newsstands was more about cutting losses than creating a growth strategy for the magazine – a sad end to an iconic brand.

5. Be a mobile leader, not a laggard

Are marketers finally ready to align ad spending with consumer media habits? Mobile advertising is growing six times faster than desktop internet; Zenith forecasts mobile ad spend will grow by an average of 50% a year between 2013 and 2016. By 2016 mobile will account for 28% of all Internet ad spending and 7.6% of total ad expenditures – leapfrogging print magazines (along with radio and outdoor) to become the world’s fourth-largest ad medium.

Everyone knows that mobile is a game-changer. Publishers need to take the lead in optimizing their websites, newsletters and other digital content for mobile.

A good first step in mobile optimization is responsive design, a technique that automatically resizes layouts based on the screen size of the device loading the content.

COLE Publishing built responsive design versions of all eight of its magazine sites serving the wastewater treatment industry, including Pumper and Treatment Plant Operator. COLE has seen a notable increase in mobile traffic and total visitors in the year since launching the redesigns. For example, on Pumper.com, traffic coming from mobile devices increased from 25% in March 2013 to 37% this past March. Monthly unique visitors have more than doubled since March 2012.

The redesign hasn’t moved the needle much on the business side yet, however. COLE President Jeff Bruss says they’re still educating advertisers on the value of mobile-specific programs, but he feels they’ve laid a foundation for growth once brands start to grasp the importance of mobile for COLE’s B2B audience.

Email is another channel ripe for mobile optimization – by both brands and publishers. More than half of UK businesses in a recent Econsultancy survey said their mobile email strategy was either “basic” (39%) or “non-existent” (22%).

Advantage Business Media (which owns eMediaVitals) redesigned the newsletter templates for all 26 of its brands after realizing that as much as 45% of its subscribers were accessing its newsletters from mobile devices. Since the responsive templates rolled out over the course of late 2013 and early this year, ad click-throughs have risen by 30%.

Got apps?

There’s still plenty of debate and confusion about whether publishers need an app strategy. Some may consider digital replicas or enhanced tablet editions to be table stakes, but they don’t really address the way mobile users access content. Instead, consider an app strategy that emphasizes utility over information.

Farm Journal’s Cash Grain Bids, for example, is a location-based app that helps farmers compare local grain prices. The RunHub app from Runner’s World magazine includes customizable training plans, route mapping and some community features for runners.

Branded apps can also be useful for any conferences you host – while opening up new advertising streams and audience engagement opportunities. DoubleDutch, a creator of event apps, claims that 56% of users access its clients’ event applications at least 10 times on average.

6. Amaze & delight your audience

In the old days, publishers acted as the ultimate gatekeepers of content, deciding what to cover with little direct input from their audience, save for the occasional survey or focus group. But the way customers interact with businesses in all industries has changed dramatically, and publishing is no exception.

The new school of thought involves actually serving your readers, based on their needs and desires. Ogden’s Welch recently said that his company’s most important innovations have centered on “accelerating use of audience feedback and digital metrics to grow larger audiences and achieve higher levels of audience engagement.”

Ogden’s brands are constantly collecting audience feedback by tracking visitors’ digital activities but also through traditional means, like weekly surveys. Welch believes it’s critically important for premium publishers to strengthen the emotional bond between their media brands and their audiences to create long-term value.

Jeffrey Rorhs, a VP for ExactTarget and author of “Audience,” spoke recently about what he calls a red velvet approach to customers. He cited five core elements that can deliver value to publishers and their audiences:

- Serve the individual. Publishers have the ability to build a large audience but leverage technology to deliver tailored service to individuals. The goal is to get direct, permission-based, push-button access to individual readers.

- Honor their unique preferences. Publishers should be leveraging predictive intelligence to personalize content, just as retailers use behavioral and transactional data to make product recommendations (e.g., If you like this you’ll also like this). Even small personalizations can create emotional connections, he said.

- Deliver timely, relevant content that improves their lives. If someone downloads a piece of content, subscribe to a newsletter or follow you on Facebook, they expect something relevant in return.

- Surprise them with access. Publishers who pull back the “velvet rope” on their business will drive attention and loyalty from their audience. Programs that target “superfans” (such as the one recently introduced by Slate) can drive reader revenue more effectively than a paywall, because readers don’t feel like they’re being charged for something that they used to get for free.

- Delight them with your humanity. A restaurant called the Melt Bar & Grilledin Ohio offers any customer that gets a tattoo featuring its logo a 25% discount for life. More than 500 have gone under the needle in the name of grilled cheese.

Personalization plays a key role in a publisher’s ability to amaze and delight readers. Publishers should continue to explore ways to repurpose content to serve ever-narrower segments of their audience. Premier Guitar’s Sprague calls it “sub-compact” publishing – the ability to slice up a niche, such as guitars, into smaller components – guitar lessons, reviews, artists, etc. – and deliver customized content to those segments.

These six strategies are not short-term fixes. A digital transformation requires time to build the skills and scale required to be successful, along with a commitment to constant experimentation and a willingness to take a few risks. But those risks are better than the alternative – the risk of falling further behind by doing nothing.

McGovern was a big thinker who saw great promise in emerging markets for technology news and information, not just in the U.S. but internationally. Just five years after launching Computerworld in the U.S. in 1967, McGovern launched Shukan Computer in Japan, kicking off a long string of global licensing deals and other partnerships that built IDG into a global powerhouse. In 1980, McGovern forged one of the first joint ventures in China by a U.S. business. In 1992, he established IDG Technology Ventures, one of the first venture capital firms in China.

McGovern was a big thinker who saw great promise in emerging markets for technology news and information, not just in the U.S. but internationally. Just five years after launching Computerworld in the U.S. in 1967, McGovern launched Shukan Computer in Japan, kicking off a long string of global licensing deals and other partnerships that built IDG into a global powerhouse. In 1980, McGovern forged one of the first joint ventures in China by a U.S. business. In 1992, he established IDG Technology Ventures, one of the first venture capital firms in China.